THE HOUSE OF MELISSINOS

(also: Melissenus In historical records throughout Europe, the Melissinos name appears in several transliterated forms, including Melissenus and Melissino. It has also been recorded as Melissen, Misili, or Messilino, as seen in Misili Del Novo or Messilino De Novo, which refer to the Melissinos branch of Demetrias. Female variations of the name include Melissene, Melissina, Melissiane, Melisane, and Melusine etc. (The plural forms are Melissenoi or Melissinoi).

ORIGINS & LEGACY

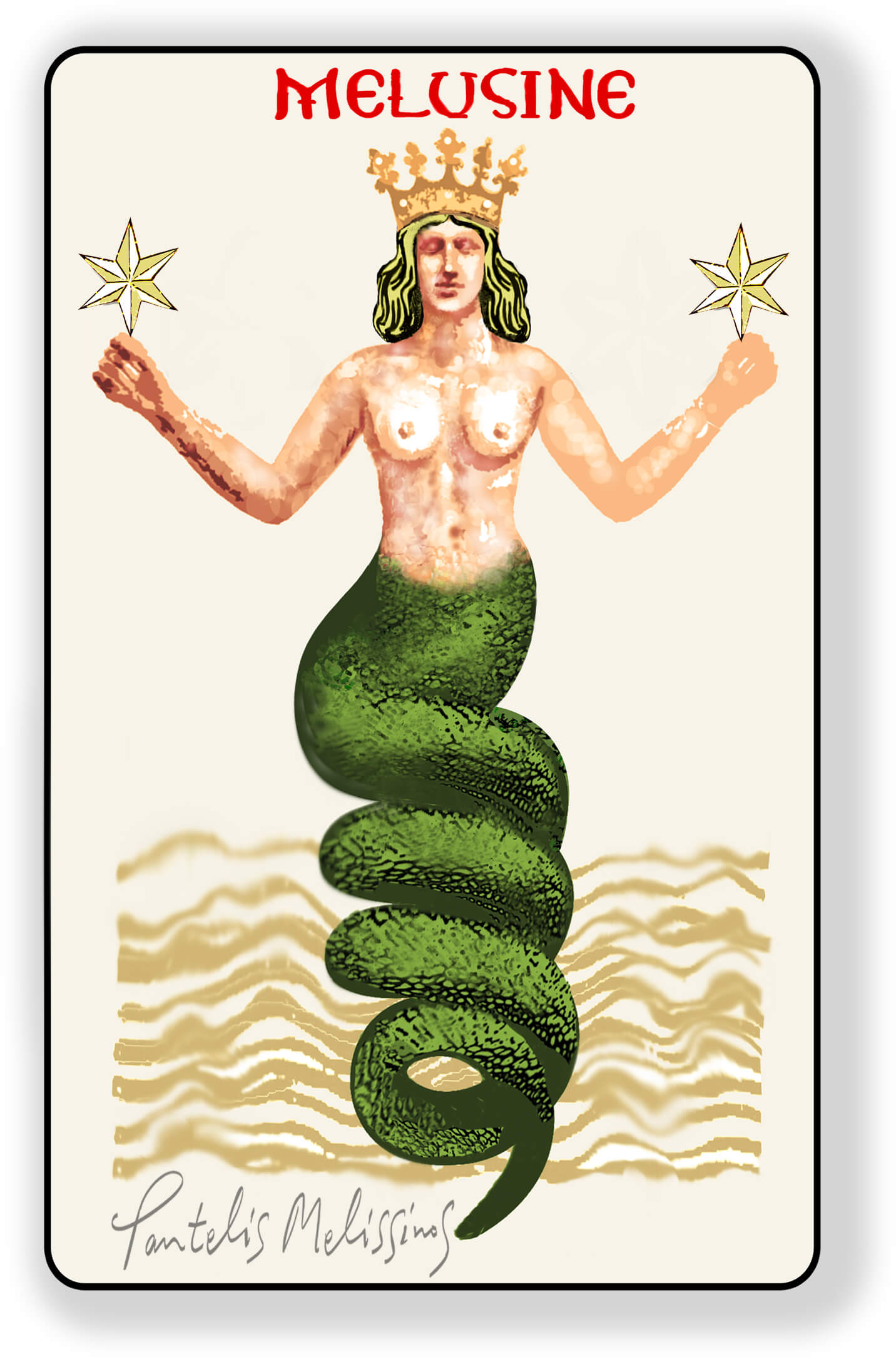

The House of the mid-8th c. Melissinoi, heralded as the oldest noble house of the Eastern Roman Empire, carved an enduring legacy in history. Revered for their ancient Greek lineage, they were, according to legend, direct descendants of Cecrops, the mythic founding king of Athens. Their story is inseparably intertwined with the Empire’s most tumultuous eras, their influence shaping its political intrigues and cultural evolution through both glory and strife. Their mark was so indelible that, by the 14th c., it gave rise to the legend of the half-human, half-dragon Princess Melusine (or Melissena), a legendary matriarch whose bloodline flowed through Europe’s most powerful royal houses, shaping the destinies of nations. Her myth is further explored in the pages that follow.

AWAKENING OF A DYNASTY – 8th CENTURY

-

Michael Melissinos (8th c.): The first known member and progenitor of the medieval Melissinos bloodline. Michael was a powerful magnate and Strategos of the Anatolikon Theme and a staunch ally of Emperor Constantine V (741–775) to whom he was closely related through his marriage to Empress Eudokia’s sister. Michael solidified his already powerful family’s influence within imperial affairs. His descendants would continue to hold high positions, both religious and secular, throughout the Eastern Roman Empire’s life and beyond.

CHURCH AFFAIRS

-

Theodotus I Kassiteras Melissinos (815–821): A direct descendant of Michael—as Patriarch of Constantinople, was involved in Emperor Leo V’s iconoclast controversy, highlighting the Melissinos family’s influence in ecclesiastical affairs. His Synod annulled the 7th Ecumenical Council’s decisions, endorsing a more lenient form of iconoclasm.

9th & 10th CENTURIES

-

In the 9th c., another Michael Melissinos, related to Emperor Michael I Rangabe (811–813), made his mark in Eastern Roman politics. Emperor Michael I Rangabe’s reign, though short-lived, was pivotal in shaping the early medieval history of the Eastern Roman Empire. His mother, Lady Maria Melissine, wife of the Great Admiral Theofylaktos Rangabe, was the key figure linking the Melissinos family to the imperial throne.

-

Callistus Melissinos (9th c.): Another significant member of the family, Duke of Cologne, in Cappadocia, led Eastern Roman forces against the Abbasid Caliph al-Mutasim. Captured and executed during the Sack of Amorium (842), Callistus, along with forty other nobles, was canonized as a saint by the Orthodox Church, marking the family’s enduring religious significance. Callistus is commemorated on March 6th each year.

11th CENTURY: STRUGGLES & AMBITIONS

-

Nikephoros Melissinos (11th c.): Amidst the instability of the Byzantine Empire, Nikephoros famously crowned himself Emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire. Choosing to relinquish the throne after a year of power struggles, he negotiated a deal to retain vast wealth and land as Caesar and played a ‘behind the scenes’ role in the empire’s politics, passing the crown to his brother-in-law, Alexios I Comnenus.

THE RECLAMATION OF CONSTANTINOPLE

-

Alexios Melissinos-Kommenus-Strategopoulos (13th c.): A key figure in the Eastern Roman Reconquista, Alexios led the forces that recaptured Constantinople from the Latins, on July 25, 1261. His strategic prowess restored the Eastern Roman Empire under Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos, marking a crucial moment in Eastern Roman history.

THE CRETAN BRANCH

-

Andreas Melissinos established the 13th-century Cretan branch of the Melissinoi when he was dispatched as part of an Eastern Roman force, comprising twelve leaders of the highest nobility, each with their armies, to enforce imperial authority on Crete during a volatile era.

EL GRECO – THE FAMILY’S ARTISTIC LEGACY

-

Domenikos Theotokopoulos (1541–1614), known as El Greco, was, according to some accounts, descended from the Constantinopolitan branch of the Melissinos House; a lineage believed to have facilitated his acceptance at the Spanish royal court. Following the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople, his family sought refuge with Melissinos relations in Fodele, Crete. The surname Theotokopoulos (meaning “son of Theotokis”) was acquired as a result of their residence on lands granted to them by their Melissinos relatives near the Church of Theotokos—rebuilt in 1323 by Michael Melissinos and his wife, Irene. El Greco’s father, Georgios, a prosperous merchant and tax collector, eventually moved the family to Heraklion, where the young artist’s journey began.

EXODUS FROM CRETE

-

In 1669, after the Ottomans conquered Crete, members of the Melissinos family’s Cretan branch fled, finding their prominence on the island. Their descendants include branches in Russia and Athens, such as the Poet Sandal Maker of Athens, whose family settled in Athens after a period on Tinos.

THE MELISSINOI OF DEMETRIAS

-

One of the Eastern Roman Empire’s most illustrious Melissinos branches—closely connected to the imperial dynasties of the Komnenos, Doukas, Angelos, and Palaiologos—were the Melissinoi of Demetrias. They were regarded as “kin to the crown” and their feudal domains included Demetrias and Mount Pelion in Thessaly. They gained prominence through Constantine (1207–1255) and Stephen Melissinos (1265–1310). In the early 14th century, Stephen Melissinos-Gabrieopoulos (1310–1337) formed the Greco-Catalan House of Melissinos-Novelles through his sister Anna’s marriage to Catalan leader Odo de Novelles. Their son, Armegildo Melissinos-Novelles, inherited and governed the family’s extensive lands, blending Eastern Roman and Catalan traditions, thus sustaining the prominence in Thessaly and beyond.

THE DUCHY OF ATHENS

-

Maria Melissene (15th century): A pivotal figure in the Duchy of Athens, Maria Melissene, daughter of Sebastocrator Leon Melissinos, became the Duchess of Athens after the death of her husband, Antonio I Acciaiouli. She ruled from the Acropolis of Athens, highlighting the family’s aristocratic standing and political influence in the late medieval period.

LAST ATTEMPT TO SAVE THE EMPIRE

-

Gregory Melissinos-Strategopoulos: Cretan noble, confessor to Emperor John VIII Palaiologos, and shrewd strategist. He played a pivotal role in the early talks at the Council of Florence, aiming to unite East and West to save the Eastern Roman Empire. Later—at the same council—he stood beside Patriarch Joseph II during negotiations with Rome. His support for Church Union during his tenure as Patriarch of Constantinople led to his abdication in 1450. He died, exiled to Rome—but the Catholic Church would later canonize him as a saint. On May 29, 1453, the Empire collapsed and Constantinople fell to the Ottomans.

MELISSINOI VS. OTTOMANS

-

In 1572, Makarios Melissinos, the Archbishop of Epidaurus, led a rebellion against the Ottoman rulers of Greece, further demonstrating the Melissinos family’s continuing influence in resisting foreign domination.

THE RUSSIAN BRANCH

-

Pyotr Melissino (1726–1797): Considered the Richelieu of Russia—a confidant of Catherine the Great, founder of the mid-1760s ‘Melissinos Rite’, forerunner of the Bavarian Illuminati—and Russian patron of Giacomo Casanova. Count Pyotr Melissino was an ingenious general and power broker, and the first to hold the rank of Artillery Officer in the Russian Imperial Army. Born in Cephalonia, he served with distinction, earning numerous honors, including the Order of St. George and the Order of St. Anna. In 1789, he became Inspector General of the Artillery, overseeing significant military reforms, and was later awarded the Order of Saint Vladimir.

-

Aleksey Melissino (1759–1813): The son of Pyotr Melissino, Aleksey was a Lieutenant General in the Russian Imperial Army. He earned recognition for his intelligence and courage, particularly during the Napoleonic Wars. Aleksey died at the Battle of Dresden after receiving multiple wounds, but his bravery was celebrated posthumously. His widow, Roxanne Mikhailova, née Princess Cantacuzino (Kantakouzenos), who tried to find his remains, in vain, erected a monument to Aleksey Melissino.

-

Ivan Ivanovich Melissino (1718–1795): Brother of the legendary General Pyotr Melissino, he too was in Catherine the Great’s inner circle—trusted, sharp, and a driving force in Russian Freemasonry, pushing Enlightenment ideals like the secularization of the Orthodox Church. As curator of Moscow University, he reshaped it from the ground up—reforming, mentoring, and overseeing the completion of its main building.

From the Eastern Roman Empire bloodlines to European legend, the Melissinos name has echoed through history—giving rise to the timeless myth of Melusine, a take on Melissena, a formidable princess of the Melissinos line.

THE INTRIGUING EVOLUTION AND LEGEND OF PRINCESS MELISSENE AS AN ARCHETYPAL FIGURE OF POWER

The archetypal 9th-century Princess Melissene, aka Melissena—a romanticized figure from the historical, noble, and powerful Melissenus (Melissinos) bloodline—stands with one foot in reality and the other in legend. Her mythical and supernatural representation exemplifies the shrewd and strong-willed Roman princesses of the Christian era, who were married off as part of diplomatic deals and alliances with emerging Western European monarchs. Some of these monarchs founded countries that continue to exist in some form today, while others have long since vanished.

The archetypal 9th-century Princess Melissene, aka Melissena—a romanticized figure from the historical, noble, and powerful Melissenus (Melissinos) bloodline—stands with one foot in reality and the other in legend. Her mythical and supernatural representation exemplifies the shrewd and strong-willed Roman princesses of the Christian era, who were married off as part of diplomatic deals and alliances with emerging Western European monarchs. Some of these monarchs founded countries that continue to exist in some form today, while others have long since vanished.

BIRTHPLACE & 14th CENTURY REEMERGENCE

Melissene’s 9th century birthplace—where the Bosporus Strait flows north to south, linking the East and the West and uniting diverse civilizations—reflected her multifaceted lineage. In the shadows of 14th-century Europe, Melissene reemerged as Melusine, a figure woven from moonlight, whispers, and mystery—an essence older than time, an otherworldly presence, epitomizing the soul of Constantinople, the heart of the Eastern Roman Empire, today known as Byzantium. To Western eyes, it was no mere city but a vision spun from gold, silk, and starlight—a realm of legend where steeples and domes kissed the heavens and wisdom flowed like wine poured by archangels. In their Western rustic world, Melissena and her city shimmered at the edge of myth, a fairy tale just beyond reach.

MELISSENE’S LINEAGE

Her ancestry intertwined with powerful medieval Roman houses and the illustrious Melissenus bloodline through her grandfather, Emperor Michael I Rangabe, whose mother, Maria Melissena, hailed from that prestigious lineage.

HER MYTHICAL FATHER

In later medieval European legends, she gains great fame and a touch of notoriety as ‘Melusine’ or ‘Melusina’—corrupted forms of the surname ‘Melissene’. In these tales, she is the daughter of ‘Elinas’, King of Albion—a Latin term for Scotland, later anglicized to ‘Albany’. However, her father’s mythical British origins may have been recontextualized, leaving inspiration from the kings of Alba Longa—an ancient Latin city in central Italy, near Lake Albano in the Alban Hills—who are celebrated in other legends as the Alban kings (Latin: Reges Albani). According to myth, these kings—shrouded in mystery and woven into a compelling saga that reverberates through history—bridge the 400-year gap between Aeneas’ settlement in Italy and the legendary founding of Rome by Romulus.

According to Roman mythology, as recounted in Virgil’s Aeneid, Rome rose around Pallantium—founded by Evander, a cultural hero from Arcadia’s Pallantium in Greece—on the future site of Palatine Hill. Notably, ‘Roma’ or ‘Rome’ also means ‘Power’ in Greek, and in a way, so does the name “Pallas”—an epithet of the goddess Athena—derived from the Greek verb ‘πάλλω’ (PAL-loh), meaning ‘to brandish’ or ‘to shake’. Dionysius of Halicarnassus reports that the ancient Romans took pride in the belief that their city was founded by Arcadian Greeks from Pallantium, led by King Evander, about sixty years before the Trojan War. Solinus corroborates this account, affirming the city’s Arcadian Greek origins. Pausanias, the Greek travel writer and geographer, recounts that Emperor Antoninus Pius granted special status to Pallantium because he too recognized the Arcadian king Evander as the original founder of the settlement that would become Rome, thus affirming the city’s Arcadian heritage.

Notably, the Arcadians were known as ‘wolfmen’, a name rooted in their mythical ancestor King Lycaon, whose very name means ‘wolf-man’. This association resonates deeply with Rome’s emblematic She-Wolf, linking the city’s origins to Arcadia—the mother of the wolfmen. Intriguingly, Melissena’s father’s name, ‘Elinas’, a variation of the Greek word ‘Έλληνας’ (‘Ellinas’: pronounced HEL-inas), meaning ‘Greek’, suggests a connection to Melissena’s Hellenic heritage.

It should also be mentioned that ΈΛλην (HEL-lin) in Greek is a prominent figure in ancient Greek mythology and the legendary ancestor of all Greeks. Today, Greeks officially refer to themselves as Hellenes or Ellines, in the plural form—dropping the ‘h’—while the singular form is Ellinas. This ‘h’ gradually faded from the name sometime after the classical period. Additionally, the description of her father as the king of ‘Alba’ or ‘Albion’ may evoke for an educated Greek speaker a linguistic connection to terms denoting ‘white’—and potentially ‘light’ as suggested by the etymology of ‘Alba’ and ‘Albion’.

A theory links the Greek term ἄλφι (AL-phee), meaning off-white barley flour, to ‘off-white’, related to ἀλφός (al-PHOS), pale white and λευκός (white). In this context, white can also symbolize The Light, cosmic energy, the life force. The same applies to the word ‘ΈΛάς’ (hel-LAS), which produces the root ΈΛλην (HEL-lin). The word ΈΛάς (HEL-las), meaning Greece, comes from the root words ‘Hel’ (also ‘Sol’) and ‘las’ (las). ‘Hel’ derives from a verb meaning ‘to shine’ or ‘to light’, often in the shape of a disc, which connects to terms like Helios (the Sun), Solana, Selene (the moon), Elani, Helen, and even the English ‘shell’. Even ‘Hel’ (as a burning hall) can be interpreted as a radiant place. The word ‘las’, meaning ‘stone’ or ‘land’. when combined with ‘Hel’, suggests the ‘land of light’. Therefore, Greece can be seen as the ‘land of light’ or, in other words, a sunny land.

MELISSENE’S NAME ETYMOLOGY

‘Melissene’, the medieval female form of the ‘Melissenus’ surname, evokes the grandeur of the Melissenus bloodline—whose name derives from ‘Melissa’, the Greek word for ‘bee’. This once-mighty dynasty held sway over Anatolia and other parts of the empire as formidable magnates, with a broad political impact that influenced Near Eastern and European affairs. It should also be noted that the name “Melissa,” often associated with royalty, originates from the Ancient Greek verb ‘μέλω’ (MEH-loh-meh). Among its various meanings, ‘μελέω’ also means ‘to care for’ or ‘to take care of’, something which meant that ‘Melissa’—daughter of King Melisseus of Crete—did when she raised, as nurse, the infant Zeus, father of the gods. Melissa’s role parallels the actions of archaic kings, whose sacred duty was to care for the future and provide for the people entrusted to them by a god or goddess.

LEGENDARY ORIGINS

During the Middle Ages, male and female members of the highly respected Melissenus bloodline stood out within the powerfulgoverning elite due to their seniority and mystifying past, tinged with supernatural overtones. According to ancient accounts, the Melissena lineage, which rose to prominence in the 8th century, traced its origins back to Cecrops, the legendary first king of Athens, who was famously depicted in Greek mythology as part-human and part-dragon.

THE MYTHICAL DRAGON

The word dragon, in Greek ‘Δράκων’ (pronounced in English as ‘THRA-kon’), means ‘The Keen-Eyed’ or ‘The All Seeing Entity’. ‘Δράκων’ derives from the Ancient Greek verb ‘δέρκομαι’ (pronounced in English as ‘THER-komeh’), meaning ‘to see clearly and understand’. In Greek mythology, dragons, depicted as enormous snake-like creatures, served as guardians assigned to protect sacred places, treasures, or important figures.

SYMBOLISM OF CECROPS

Cecrops’ serpent form symbolizes the swirling primal chaos and the All-Seeing Universal Mind within it—an unseen force shaping the cosmos. In contrast, his human half represents humanity’s intellectual potential to achieve wisdom through reason, enabling the navigation of these cosmic forces.

MELISSENA’S EVOLUTION INTO MELUSINE

Over time, Melissena—an archetypal Eastern Roman princess—evolved into the legendary Melusina, (or Melusine), a distorted Westernized echo of her true name. In European myths, her dual nature transformed, shifting from the cosmic symbolism of Cecrops’ half-human, half-serpent form to interpretations shaped by local traditions. Her human side became a symbol of beauty, nobility, and civilization, while her serpent form embodied magic, mystery, and a gift for sowing chaos through Roman intrigues. As her legend spread, each region reimagined her story, leaving only fleeting traces of her Eastern Roman origins.

INFLUENCE ON EUROPEAN ROYAL HOUSES

The mystique surrounding Princess Melissena’s enigmatic Medieval Roman royal lineage led numerous Western European royal houses to claim her as an ancestor, eager to align themselves with her storied heritage. These include the Lusignans, the House of Luxembourg, Count Raymond of Poitiers, the Counts and Dukes of Anjou, the House de Plantagenet, the Angevins, the Houses of Lancaster and York, Richard I of England, and various other European royals and royal houses. They all sought royal legitimacy by tracing their lineage back to the illustrious Greco-Roman civilization, the Roman Empire, and its Christian phase.

THE RESURRECTION OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE

In the 4th century A.D., the world, in awe, witnessed a dramatic twist: Emperor Constantine ‘resurrected’ the Roman Empire through a masterful blend of political and military savvy combined with the use of a religious narrative, a divine drama, designed to manipulate the emotions of the masses and serve his ambitious agenda. During periods of significant upheaval, a major reset often becomes necessary, requiring its own ‘religion’ to usher in a new era. In such times, a new religion plays a crucial role in establishing the new framework for a global order under an all-powerful authority with a near-sacred dimension, much like that of Constantine the Great. In Constantine’s grand Roman revival, the new religion, Christianity, took center stage, starring Jesus Christ in the leading role as humanity’s ultimate hero and savior. This supernatural narrative, blending earlier myths from the East and West, depicted a resurrected Jesus, the Son of God, crowned as the universal king. The portrayal of Christ strikingly mirrored that of Emperor Constantine, whose cunning and strategic brilliance earned him global recognition as “Constantine the Great”.

THE UNIFYING FACTOR

This new politically driven religious narrative became the empire’s unifying force, marking the end of the old world. Greek ideals rationalism and science were overshadowed by dogma and imperial ambition, ushering in a dark era where fear and superstition suppressed progress and delayed Enlightenment.

FEAR: A TOOL FOR CONTROL

Fear is a powerful tool used by those in power to control populations, as it preys on the irrational and instinctive sides of human nature. Plagues, the “Fires of Hell,” looming wars, and natural disasters — framed as punishments for human misbehavior — are some of the most historically common fears used to control the public. When fear takes hold, reason takes flight, and people surrender to survival instincts and impulse—falling prey to those who exploit this vulnerability for their own ends.

THE ‘ICXC NIKA’ MOTTO

Constantine’s imperial emblem, with the Greek acronym ICXC NIKA overlaid on the quadrants of the equal-armed Greek cross—a symbol of universal energy—conveys a dual meaning: ‘Jesus Christ Conquers’ (IHCOYC XPICTOC NIKA, pronounced ee-ay-SOOS Krees-TOHS NEE-kah) and ‘Power Conquers’ (ICXC NIKA, pronounced iss-KEES-nee-kah). The latter carries pre-Christian Greek philosophical significance, known in Latin as Sol Invictus (the Unconquered Sun). The sun, symbolized in this emblem by the Greek Cross and paired with the obscure acronym, signifies Triumph Through Alignment with The LIGHT—the energy of the universe. A handful of European monarchs, privy to this hidden meaning, sought empowerment through connections to ancient Eastern Roman bloodlines.

CULTURAL APPROPRIATION

The glamour and mystique of the medieval Eastern Roman Empire led some to appropriate its name and culture, rebranding it as ‘Byzantium’ while calling their own lands the ‘Holy Roman Empire’.

MELISSENE’S MEDIEVAL LEGEND IN FEW WORDS:

King Elinas of Albion marries the fairy-like Pressina, with the condition that he must never see her giving birth. But when he breaks this vow, Pressina vanishes, taking their triplets with her. One of the triplets, Melusina, grows up and seeks revenge by imprisoning her father. In her grief, her mother curses her to transform into a serpent from the waist down whenever she takes a bath. Later, when Melusina marries Count Raymond, she makes him promise that he will never see her bathe. Driven by jealousy, he spies on her and, upon seeing her serpentine form, flees, believing her to be a demon. Now a wandering spirit, Melusina roams Europe, seeking love in the hope of restoring her human form. The legendary Greco-Roman saga—of Athens, Sparta, Alexander the Great, and Rome—along with its civilization and aura, inspired the myth of Melissena: a half-human, half-dragon figure embodying secret knowledge, might, refinement, beauty, and supernatural powers. Her myth spread through 14th-century European courts, like wildfire.

Pantelis Melissinos, Athens 2024